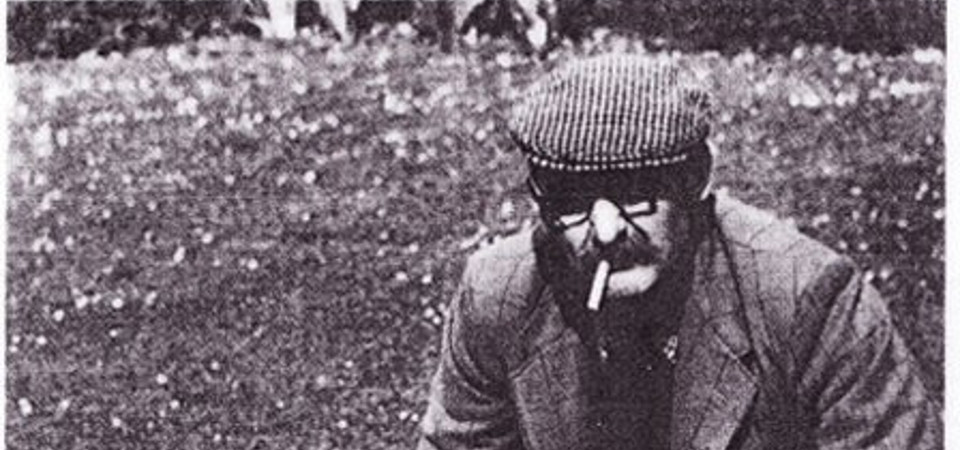

Thomas Octave Murdoch – T.O.M. – Sopwith was first and foremost an engineer throughout his long life.

Born in January 1888 he lived to be 101, dying at his home near Romsey in January 1989.

As a young man before the First World War his primary interest was in aircraft and flying and he became famous at a comparatively young age with his pioneering activities in these fields both in England and in America.

His first flight was in 1910, and within a month he had earned his pilot’s licence, No. 31. He began manufacturing aircraft and was involved with Sammy Saunders in 1913 in the building in East Cowes of the Bat Boat, the first really successful seaplane.

Finest fighting aircraft of WWI

His new company, Sopwith Aviation, produced further well-known designs and in 1914 his Sopwith ‘Tabloid’ won the second Schneider Trophy race at Monaco.

During the First World War, perhaps his company’s two most famous designs were the Sopwith Pup and the Sopwith Camel, the latter probably the finest fighting aircraft of the WWI and, arguably, of all time.

Although a post-war slump in the aircraft market took a toll on his company, he managed to give it a highly successful new direction and name along with his chief test pilot, Harry Hawker.

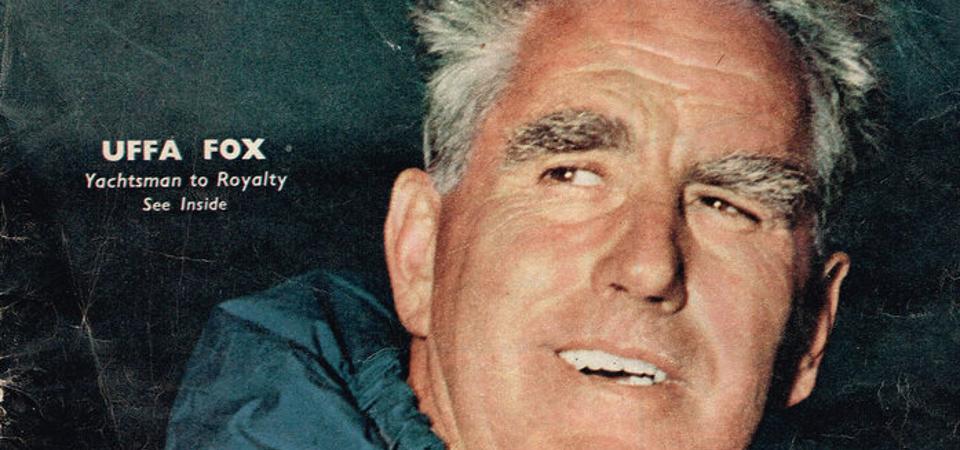

Love of sailing and powerboat racing

Sailing had been one of Sopwith’s interests since boyhood and, starting in dinghies, by 1909 he was co-owner of a dilapidated 166 ton schooner, Neva.

He was also addicted to powerboat racing, in those early days so much an important sporting activity with its associated development in both engine design and manufacture. So many names that would become famous as car manufacturers began by building powerboats, Wolsey, Daimler, Mercedes, Napier.

Award-winner

In 1912 he won the prestigious British International Trophy in Maple Leaf IV, built by Sammy Saunders, and repeated that win two years later with a world record time of 48 knots.

In the decade after the War he also owned a series of ever larger diesel yachts, culminating in the ‘30’s in the magnificent Philante.

He was regarded as the best British 12m helmsman and was Class champion in 1928, 1929 and 1930 with his 12m Mouette, built for him by Camper and Nicholson, whereupon he was elected a member of the Royal Yacht Squadron.

America’s Cup

Tom became absorbed in the challenges by Sir Thomas Lipton for the America’s Cup, and on the death of Lipton in 1931, he bought Lipton’s J-class yacht, Shamrock V.

For two years he raced her around the Solent, being unusual as an owner in that he steered his own vessel, instead of merely relying on a professional skipper.

The birth of Endeavour

In 1933 he commissioned Charles Nicholson to design and build in Gosport a new J-class yacht, Endeavour, in order to challenge the Americans for the series in 1934.

This series was one that was so hotly contested that it nearly returned the America’s Cup back to Great Britain.

Endeavour, racing against Harry Vanderbilt’s Rainbow, was widely considered to be the faster of the two. However, several controversial events during racing robbed Sopwith of victory, and he went home a disappointed man, vowing never to challenge again.

Crushing defeat for Endeavour II

He did try again, in 1937, but this time his new boat, Endeavour II, came up against the American defender, Ranger, generally agreed to be the fastest J ever built, and this time defeat was crushing.

Thereafter the heavy demands of aircraft manufacture during the Second World War put a end to Sopwith’s maritime activity, his final racing yacht being the 12m Tomahawk in 1939.