It was the early hours of 5 May 1942, despite the darkness of the night the burning fires on both sides of the Medina lit up the streets of Cowes and East Cowes like a brilliant orange sun reflecting of the underside of the smoke and dust that hung in the sky like a thick circling and rising smog.

The pavements and tarmac were littered with debris, smashed bricks from entire walls that had slammed to the ground, shattered roofing timbers and slates that skittered away to fragments.

Between the rubble staggered the survivors, clutching one another, stunned, dazed, and unable to comprehend the scene and the noise of the roaring conflagrations, the engines of the fire pumps, the pounding fire of the guns of the Polish warship and the cries of relief as loved ones discovered one another and the grief of those who could not.

National Fire Service, Division 14d

Threading their determined way through the maelstrom moved an army of rescuers, Fire Guards, First Aid Parties, Voluntary Aid Detachments, French and Polish sailors and members of the National Fire Service, Division 14d, the Isle of Wight’s own.

The wave of attacking aircraft had withdrawn back to Northern France as two of the NFS firemen, 19 year old Fireman Colin Henry Weeks and his best friend Leading Fireman Herbert James Dewey, both from the Ryde detachment, were making their way, under orders from Company Officer Max Heller, to take the opportunity to go to the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service canteen wagon stationed at the corner where Clarence Road turned in to Minerva Road beside Marvin’s Yard, and grab a well earned cup of tea and a sandwich.

Old friends who shared a love and gift for music

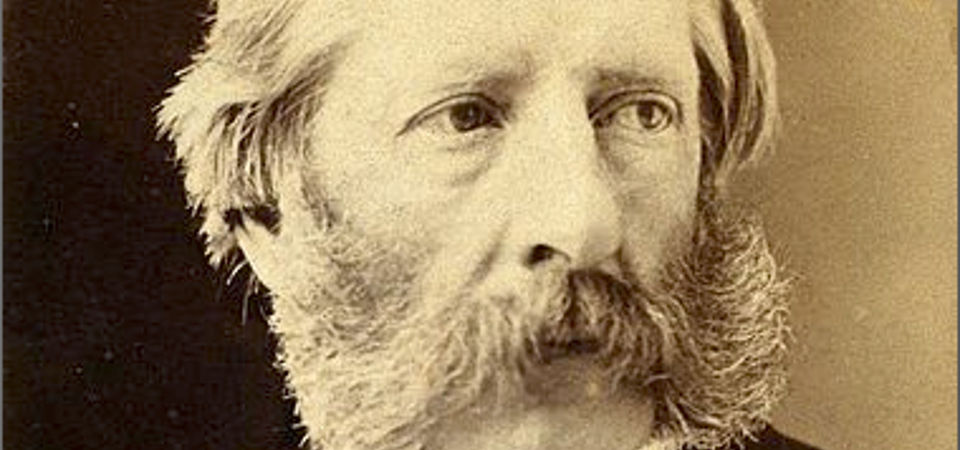

Colin and Herbert had been friends long before the government required a ten-fold increase in fire-fighting services to tackle the worst of the enemy aerial assaults.

Whilst twenty years separated them they shared a love and gift for music, Herbert, always known as Bert, being well known in the district for the shows he put on in the town and Colin for often performing at the piano.

It was a rendezvous with his piano tutor Mr Toogood that took Colin to the Town Hall on 7 June 1940 whereupon, being aware of his presence, his father Mayor – HWO Weeks – asked a clerk to direct his son to the Mayoral parlour when his lesson was over. Colin duly complied with a self-confessed feeling of ‘what have I done now’.

A pound a week

Mr Weeks Sr, was aware that the Auxiliary Fire Service was in need of a competent clerk and knowing his son’s administrative skills and capability on a typewriter he left it to Colin to make the decision whether or not to take the job but there’s little doubt that some fatherly pressure being applied.

Colin attended the temporary wartime station and training centre in Edward Street the next day and accepted the position, admitting in his diary,

“The reasons for my coming to the decision were not those of a patriot, doing his little bit for King and Country, far from it, I was hard up, earning a meagre allowance of five shillings a week and now I was offered the imposing figure of a pound per week.”

Bitten by the bug

He began his diary, dedicating it to his comrades in the fire service, soon after taking up his role and was known for sitting at the typewriter recording his fire service events between his required duties.

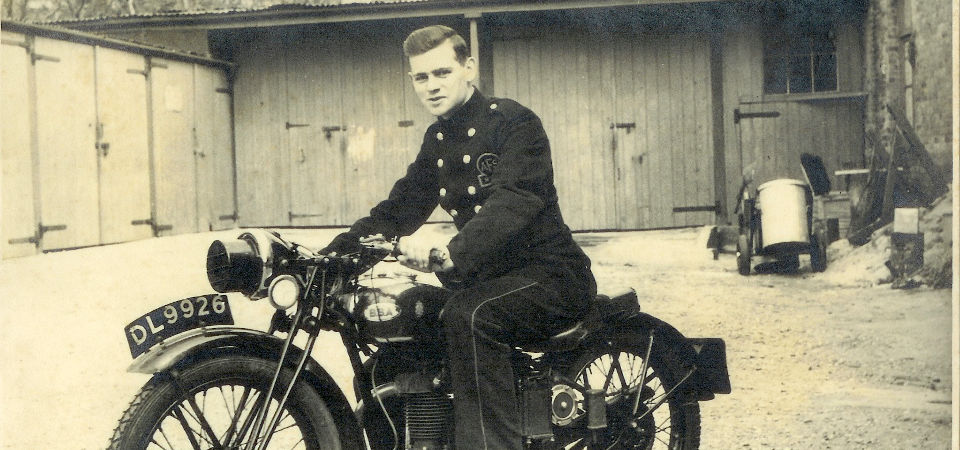

Admitting that he’d previously had no interest in the fire service and even had a particular fear of fire, he recorded that by August the fire service bug had bit him at his office desk and he began training as a fireman. He also learned to ride a motorcycle (pictured above) and spent much of his time scooting from one location to another as a service messenger.

Dedicated firefighter

By now, even when officially off duty, at the sound of the siren he’d grab his uniform and helmet and cycle madly to Edward Street and often as not, clamber aboard the rear boards of Jack Fountaine’s 2-ton Chevrolet coal lorry that was adapted as a fire service vehicle once the day’s coal deliveries were complete.

He describes scenes across the town and district unimaginable, one particular event affecting the St John’s area involving thousands of 1kg incendiary bombs. The claim was not as wild as it at first seemed as by now the Luftwaffe had developed containers that could carry several hundred of these devices and a bomber could carry several of the containers.

Fascinating insight

The descriptions of disaster are interwoven with the type of escapades and humour that one would expect from a teenager, but given the contrast of the days of action including exposure to some grisly and horrific events his apparent irreverence can be understood.

Suffice to say by May 1942 he had, for his tender age, experienced the inconceivable.

Unparalleled attack

The strength of the Luftwaffe’s attack that began late in the night of 4 May was unparalleled on the Island and completely unexpected, although the sudden arrival a week earlier of masses of new pumps and equipment compelled some to conjecture that intelligence of the attack had been gained.

The Air Raid Precautions headquarters in Newport was the communications hub for the disposition of services to come to the aid of the stricken town’s but by the early hours of 5 May, despite an earlier attempt to hold back at least one fire pump in each major sector, the duty warden in possession of information regarding the scale of the devastation promulgated the message to send all Islandwide resources to Cowes and East Cowes.

Buried side by side, as they died

As Colin and Henry took the chance to take a deep breath and refuel at the WRVS canteen the wholly unexpected second wave of Luftwaffe bombers approached from the south.

They were killed when the first stick of bombs made a direct hit on the van.

Colin and Herbert were buried side by side, as they died, in Ryde Cemetery three days later.